متن انگلیسی تخصصی دانشجویان رشته علوم انسانی (PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY)

PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY

(i) It would be absurd to attempt a definitive account of philosophy of history in the first chapter: it is, after all, the subject of the whole book. Very little can be conveyed about philosophy by explicit statements, practically nothing by a few short ones at the outset. As Kant pointed out, the place for definitions is the end not the beginning of philosophy books. Even in their proper place they are rarely intelligible by themselves in isolation from everything that has led up to them. All the same, in spite of such fully justified reservations, there is still a case for some preliminary characterisation of what we shall be concerned with, an account which might fix the starting point and indicate the nature of the expedition even though it cannot fully determine the route to be followed. Everything that can be said at this early stage has to be regarded as open to revision and qualification in the light of what will come later

Philosophers of history, at least those writing recently in English, have mainly been concerned with the significance and truth of historical statements, the possibility of objectivity, with explanation, causation and values. Their questions correspond closely to those asked in philosophy of science; indeed philosophy of history, whatever may have been the case among its first practitioners, is nowadays most commonly conceived, on the analogy of philosophy of science, as the philosophical study of a distinctive and rich field of intellectual enquiry. The questions of the philosophies of history and science are, moreover, closely related to those considered, usually in more general forms, in epistemology (theory of knowledge) and ethics (moral philosophy, philosophy of value). Nor is this overlapping and interrelatedness accidental: philosophy is one subject. It is an activity, prompted by a distinctive form of curiosity, which may be carried on in relation to a variety of subject matters-morality, art, religion, science, history, etc. -- but which remains fundamentally the same activity throughout. Divisions between different 'branches' of philosophy are in the subject matter (partly determined, no doubt, by academic tradition, con- venience, division of labour - for nobody can do everything): they are not intrinsic to philosophy. There may be all the difference in the world between morality, science and religion: but the philosophers of them are engaged in fundamentally the same sort of enquiry

It follows that philosophy of history should not be carried on in isolation from other branches of philosophy. It is not in any sense vain repetition that, say, objectivity and explanation by subsumption under laws should be treated in the philosophies of both history and physics; indeed it is inevitable that they should be. It would be absurd to discuss such topics in any field without awareness of their place in others. Much confusion has arisen in philosophy of history from lack of this awareness. Philosophy needs to be explicitly comparative, otherwise there is the risk of taking as distinctive of one subject a feature common to others, or of dismissing a subject for falling short of an ideal that is nowhere attainable. History, especially in the matters of objectivity and explanation, has suffered a great deal in the latter way-sometimes, be it said, at the hands of historians as well as philosophers. For if, as is being claimed, philosophy really is one subject, practising historians, despite their relevant knowledge, cannot be guaranteed immunity from error in philosophy of history

Why should history be singled out for philosophical consideration? In principle, no doubt, philosophical questions can be asked about anything: but there are no philosophies of sporting journalism or stamp collecting. The answer, as already suggested, must be that history is a distinctive and rich species of intellectual endeavour. On the face of it, it is an interesting subject for comparison with science, or, more exactly, with the natural and social sciences, for it must not be assumed that they are all the same. Physics, usually classical, Newtonian physics, is too often taken as the model for the natural sciences, and sometimes even for the social sciences too. History seems to resemble the natural sciences in seeking truth and explanation, but to differ from them in that the truths and explanations it seeks (or can get) are different – singular not universal truths - which raises difficulties about verifiability and sig- nificance, and, it may be, explanations in terms of purposes not laws. Comparisons and contrasts between history and some of the social sciences are more promising still; for, like history and unlike the natural sciences, they are concerned with human actions, intentions, purposes; but, like the natural sciences and probably unlike history, they seem to be seeking universal truths and explanations in terms of laws.

Somewhat more speculatively, history may be judged philosophi- cally interesting as falling between the sciences and literature. History has on occasion been claimed to be a science - 'no more and no less'; but it has for much longer been regarded as an art, with Clio as one of the Muses. Historians tell stories, at least they all used to and many still do; and these may be valued, as are novels and plays, for the insights they offer into human character and behaviour. But with this similarity there is the enormous difference that the historian's stories, like the con- clusions of scientists, purport to be true. History differs from im- aginative literature in offering not truth-likeness or truth to life, but truth; not what might or could have happened, but what did.

There is not, of course, very much enlightenment to be gained from comparisons and contrasts in terms as broad as these. But there is considerable interest in attempting to clarify them and to formulate with more precision what the resemblances and differences are. The interest is philosophical, different from and wider than an interest in history as such. It is possible to interest oneself in history without asking philosophical questions about it. Philosophy of history lies outside the professional concerns of historians. But the converse is not true. A philosopher falls short as a philosopher if he refuses in principle to consider history. It is part of the task of philosophy to look at history and try to place it in relation to other fields of enquiry and concern

(ii) The conception I am outlining of the philosophy of history is often further explicated by saying that, like the rest of philosophy, it is a 'meta-' or 'second order' study. History is the 'first order' study of past actions, events, situations: philosophy of history the study of the study of these topics. Similarly the physicist studies the transactions of atoms or sub-atomic particles; the philosopher of physics studies, not these, but certain rather general features of the way the physicist studies them. Whilst the physicist seeks to establish truths about ultimate particles and to find theoretical explanations for them, the philosopher rather enquires into what counts as evidence or explanation in physics. The same is true of moral philosophy and philosophy of religion, of which the subject matters are not academic subjects in the way physics and history are. The moralist or moral agent makes moral judgements, religious believers used to assert the existence of God and presumably still pray to Him – the philosopher, as such, does none of these things. His interest is in moral judgements and religious assertions and practices, how they could be supported or discredited, how they relate to judgements, assertions, practices of other sorts. He does not, as such, have to participate in the subjects or activities he studies

The second order character of philosophy is the basis of the defence to the common charge that philosophers presume to meddle in other people's subjects, usually without having done the preliminary hard work - as if scientific truth could be acquired in an armchair instead of a laboratory, virtue without experience of life, salvation without prayer and fasting. Historians have been known to remark ironically that they are content with the humble task of finding out what did happen: not for them the more exalted philosophical task of proving that it had to happen. Professor G. R. Elton, in a similar frame of mind, complains of the irrelevance of philosophy to history: 'It [his book] embodies the assumption that the study and writing of history are justified in themselves, and reflects a suspicion that a philosophic concern with such problems as the reality of historical knowledge or the nature of historical thought only hinders the practice of history' (1967, p. vii). Compare p. 100, where he writes of 'serious philosophical problems involving the very question whether historical explanation . . . is possible at all. This need not concern us, except to note that what troubles the logician and the philosopher seems least to worry those even among them who have had some experience of what working among the relics of the past means.' (Cf. also J. H. Plumb, 1969, p. 104.) Elton is not simply saying that philosophers make mistakes about history, though he doubtless thinks they do; his point is rather that philosophical concerns are unimportant, if not positively harmful, to the practice of history.

Whether historians are indeed wholly proof against the seductions of philosophical curiosity does not matter. The fundamental rejoinder is rather that philosophers of history are simply not trying to do history at all, and that it is, therefore, of no necessary concern to them that their activities help, hinder or otherwise bear upon the practice of history. Conceivably historians sometimes get entangled in philosophical thickets from which philosophers might extricate them, but even if they

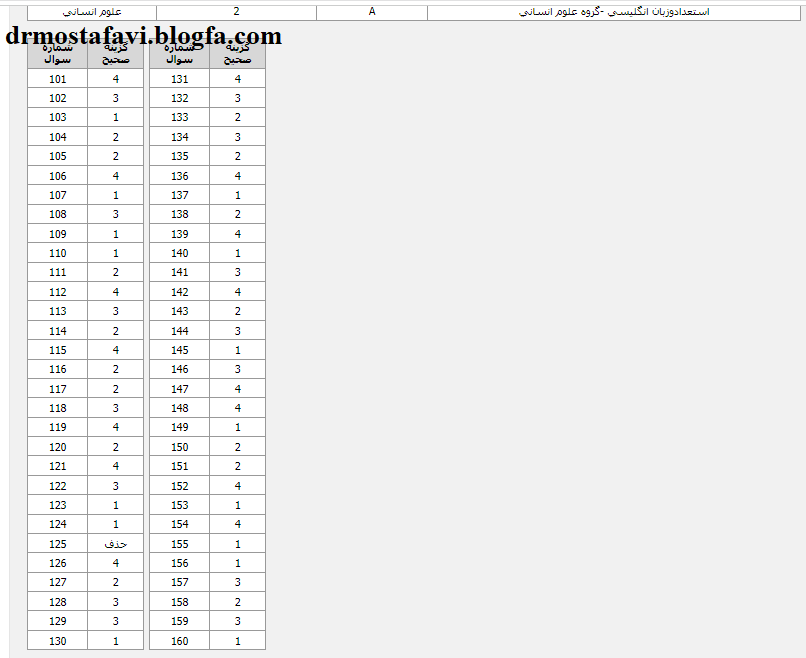

ص155

** قسمت هایی که با رنگ بنفش مشخص شده اند در کتاب زبان انگلیسی برای دانشجویان انگلیسی علوم انسانی II امده است

منبع: کتاب Knowledge and Explanation in History: An Introduction to the Philosophy of ...

By Ronald F. Atkinson

راهنمای آزمون ارشد و دکتری رشته علوم قرآن و حدیث+مطالب آموزنده قرآنی و حدیثی+علایق شخصی

راهنمای آزمون ارشد و دکتری رشته علوم قرآن و حدیث+مطالب آموزنده قرآنی و حدیثی+علایق شخصی